Hydropolitics in the Ganges and Mekong basins: Beyond the Dichotomy of ‘Conflict’ and ‘Cooperation’

Devika Nambiar

Abstract

Human societies have disputed, connected, and negotiated over water resources since time immemorial. This interplay between water resources and politics is studied through the discipline of hydropolitics. While dominant discourses in hydropolitics lean on the ‘conflict or cooperation’ dichotomy to explain state behaviour, historical accounts of hydropolitics call for a more inclusive and comprehensive approach. This essay will expand on this observation by drawing on two cases of hydropolitics in Asia – the Ganges and Mekong basins. It will demonstrate that in place of understanding state behaviour through the rationalist ‘conflict or cooperation’ dichotomy, utilising a constructivist lens focusing on the domestic political makeup of the upstream riparian state – i.e., India in the Ganges and China in the Mekong – provides a more suitable and accurate explanation of state behaviour and policy in hydropolitics.

Introduction

Water is an integral and irreplaceable element to sustaining human life as we know it. In today’s world, the worth of water extends well beyond its function as an enabler of life. From energy production to crop cultivation, water is an essential component to continuing and advancing the living systems developed by humankind over years. In a world where water bodies are unevenly distributed, and, in most cases, shared by two or more sovereign states, access to water becomes a highly political subject. Here is where the discipline of hydropolitics comes in.

Hydropolitics is a novel field of study that surfaced as recent as the 1990s. Much of the literature on hydropolitics is dominated by the positivist theoretical schools of liberalism and realism. These discourses have popularly conceptualised hydropolitics as either ‘conflict’ or ‘cooperation.’ However, historical accounts of hydropolitics have proved otherwise, raising doubts on the suitability of such a dichotomous lens for understanding state behaviour in hydropolitics.

This essay will focus on two key historical accounts of hydropolitics in Asia: India in the Ganges basin and China in the Mekong basin. It will demonstrate that in place of a rationalist outlook on hydropolitics, adopting a constructivist lens provides a more satisfactory understanding of state behaviour. Abiding by the parameters of this study, a review of the domestic political makeup will serve as said constructivist outlook. Therefore, the essay will prove that a review of the domestic political makeup of India and China provides a more sophisticated and appropriate understanding of state behaviour in the Ganges and Mekong basins than popular rationalist theories can.

Hydropolitics and the myth of ‘water wars’

Cooperation and conflict between riparian communities over shared water resources have been occurring since the Neolithic age. As noted by UNDESA (2014), one of the earliest recorded negotiations between communities is that between the two Sumerian states of Lagash and Umma to resolve the dispute over the Tigris River. Nevertheless, the discipline of hydropolitics is relatively new. Much like the case of other natural resources, the study of transboundary water politics gained prominence only in the 1990s.

Hydropolitics is commonly defined as “the systematic study of conflict and cooperation between states over water resources that transcend international borders” (Elhance, 1999:3). It is important to note that this definition is not inclusive of all components of the discipline. As noted by Turton, hydropolitics is not exclusively state-centred. Rather, it is “the systematic investigation of the interaction between states, non-state actors and a host of other participants, like individuals within and outside the state, regarding the authoritative allocation and/or use of international and national water resources” (2002:15-16).

However, the dominant discourse steering studies on hydropolitics focuses on linear notions of state behaviour and can be characterised as the ‘water wars’ narrative (Stucki, 2005; Solomon and Turton, 2000). The ‘water wars’ narrative is primarily influenced by the neo-Malthusian line of thought, where the scarcity of a shared-resource is expected to trigger conflict between two or more communities. In such a context, states view the access to water as a “matter of national security” (Gleick, 1993:79), and “will take up arms to defend access to a shared river” (Dinar et al., 2007:139). Gleick claims that historically, “water and water-supply systems have been the roots and instruments of war” (1993:84). He uses multiple accounts from history to support this claim, including that of the diversion of the Jordan River contributing to the Arab-Israeli War in 1967, and the bombing of irrigation water-supply systems in Vietnam by the United States in the late 1960s. He also speculates that as the demand for water increases with global population growth, these water-related tensions are likely to intensify.

Despite its popularity and sensationalist appeal, the ‘water wars’ narrative stands weak when it comes to empirical backing. As noted by Dinar et al., “the last time water has played the main role in instigating a war was 4,500 years ago” when the Sumerian states of Lagash and Umma went to war over the Tigris River (2007:139). This does not mean that riparian states have not engaged in violent or non-violent disputes ever since. In fact, between 1918 and 1994, there have been seven recorded instances of armed or near armed skirmishes involving water resources (Wolf and Hamner, 2000:57). However, most of these skirmishes have occurred in the Middle East, where the political instability and water scarcity is of a magnitude that is arguably different to the rest of the world (Dinar et al., 2007:139). Moreover, the majority of the actions taken in regard to water disputes involved mild verbal disagreements or hostility (Carius et al., 2005). Hence, as suggested by the neo-Malthusian and neo-realist schools, riparian states may dispute over shared waters but these disputes have never in recorded history escalated to war since 2500 BC. Instead, it has been contained to military skirmishes, or verbal hostility. To claim that competition over water leads to war is an overstatement, making the ‘water wars’ narrative inaccurate and misleading.

The reality of hydropolitics

Defying the ‘water wars’ thesis, history has noted that riparian states are more inclined to settle the issue with codified international treaties than armed conflict (FAO, 1984; Wolf and Hamner, 2000; Dinar et al., 2007). As recorded by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, 3,600 water treaties were signed in the period between 805 AD and 1984 (FAO, 1984). In addition, Carius et al. claims that “some of the world’s most vociferous enemies have negotiated water agreements or are in the process of doing so, and the institutions they have created often prove to be resilient, even when relations are strained”(2005:85). Examples of such instances include the Indus River Commission between India and Pakistan, which remained strong through two major wars between the countries.

Scholars of transboundary water relations have made several observations regarding cooperation in hydropolitics. Among them, two major deductions on the nature of transboundary water cooperation stand out. Firstly, cooperation is varied and volatile in nature. To elaborate, cooperation is not steady or consistent. It is evolving and can be of varying degrees of intensity and effectiveness at different points of time (Daoudy and Kistin, 2008). Hence, it does not always indicate a positive outcome or interaction between states. Secondly, cooperation is not an end. In the context of hydropolitics, it is possible for one to misconstrue cooperation as an end rather than “an on-going and non-linear process” (Mirumachi and Zeitoun, 2008:303). However, the occurrence of cooperation is not by itself a ‘goal’ and does not indicate that the optimal solution has been reached at. Instead, as suggested previously, its influence and effectiveness are prone to change over time.

These two characteristics of cooperation suggest that the occurrence of a cooperative event does not indicate that the possibility of conflict is entirely overcome. Instead, a combination of conflictive and cooperative interactions co-exists side by side in hydropolitics. This is exemplified by the transboundary water relations in the Jordan River basin, where despite the riparian states engaging in cooperation and signing numerous treaties, incidents of conflict and tension continue to exist.

Hydropolitics in Asia: The cases of the Ganges and Mekong basins

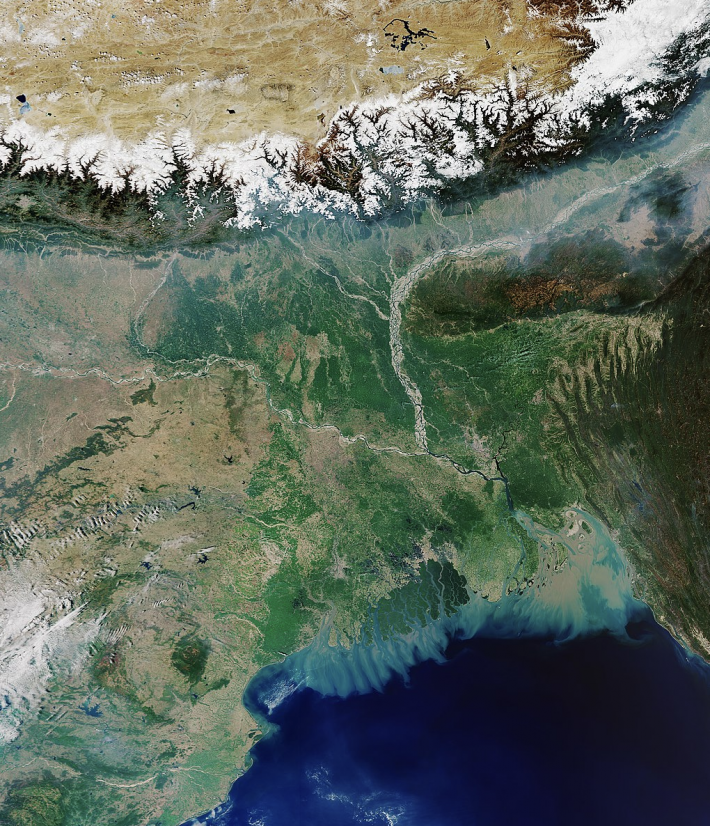

Located on either side of the Himalayas, India and China are geographically blessed with numerous waterbodies. Among them, the Ganges and Mekong rivers hold a significant position in the hydropolitics of both countries. The following section will provide an overview of hydropolitical interactions in the Ganges and Mekong basins. Each case study will outline the events of conflict and cooperation with a focus on the upstream hegemon’s behaviour towards downstream riparian states.

The Ganges River basin

The headwaters for the Ganges River originate from the southern slopes of the Himalayan range in China. It then cuts across the northern region of India and consolidates with the Brahmaputra and Barak Meghna rivers in Bangladesh before finally flowing into the Bay of Bengal.

Hydropolitical tensions in the Ganges basin began when India presented plans to build the Farakka barrage on the Ganges in 1951. Pakistan, which included the current state of Bangladesh under the name ‘East Pakistan’ until 1971, objected to this proposal claiming that the dam would alter the flow of water to East Pakistan, and would severely damage the region (Hossain, 1998). Although both countries did not experience significant shifts in water interactions in the following two decades, the riparian relations in the Ganges basin transformed quickly with the formation of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh in 1971. Both India and Bangladesh came together to establish the Joint River Commission in 1972 as a show of transboundary water cooperation. However, during its initial years, disputes over the Farakka barrage was specifically excluded from the commission’s arena of work (Swain, 2004).

In 1975, India successfully completed the construction of the dam and the Farakka barrage assumed operation. Expectedly, Bangladesh reached out to international platforms to raise concerns regarding reduced water flow to its land (Cascao et al., 2015). Although India paid little attention initially, both countries came to a conditional agreement to share the Ganges in the same year. Yet, the following years witnessed an explicit violation of the agreed terms by India, whereby the country began diverting water without consulting with its downstream neighbour. The Bangladeshi government expressed its opposition to Indian actions stating that “failure to resolve this (Farakka) issue … carries with it potential threat of conflict affecting peace and security in the area and region as a whole” (Swain, 2004:61). Eventually, in 1977, both countries agreed on another interim five-year agreement to share the water.

Due to excessive flooding in Bangladesh, increased upstream withdrawal during dry seasons, and, most importantly, the expiration of the former agreement, a new agreement was reached in 1996 (Swain, 2004). Both countries signed the ‘Treaty between the government of the Republic of India and the government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh on Sharing of the Ganga/Ganges Waters at Farakka.’ This treaty, unlike its predecessors, extended over a longer period of thirty years, and assured a more flexible approach and plan to share the Ganges waters (Dinar et al, 2007).

The treaty marked a turning point in bilateral relations for both countries. However, this optimism did not last for long. Low flow during dry season and flooding during the wet season stirred tensions in Bangladesh as early as 1997. In addition, again, India was repeatedly accused of pollution and withdrawing more water than what was prescribed in the treaty (Dinar et al., 2007). When Bangladesh attempted to engage in dialogue about these issues, India was accused of showing little interest to cooperate (Cascao et al, 2015).

Scholars have criticised the treaty itself for favouring India, and for lacking a clear dispute resolution and arbitration mechanism (Rahaman, 2009). These shortcomings have allowed India to continue its unilateral pursuits, which includes dam construction in the Teesta River, and plans to divert and link Ganges waters to other river bodies within the country (Faisal and Nishat, 2000). The lack of significant transformations in the terms of the treaty has made sure that the hydropolitics between India and Bangladesh in the Ganges basin has not significantly changed since the thirty-year treaty was signed in 1996.

The Mekong River basin

The Mekong River originates from the Tanggula Shan Mountains in the Tibetan Plateau and flows through the southern Yunnan Province in China before forming stretches of the borders between China and Myanmar, Myanmar and Laos, and Laos and Thailand. It then cuts through Cambodia before dispersing into the South China Sea at the Mekong Delta in Southern Vietnam.

Rivalry and tensions between the countries in the Mekong region can be traced back to pre-colonial times. Yet, keeping aside centuries-old animosities, the lower basin riparian states recognised the hydraulic potential of the basin through means of peaceful joint action as early as 1952 (Dinar et al., 2013). In the following years, the region witnessed numerous attempts to enforce cooperation to reach its hydraulic potential. This included the signing of the Mekong Statute and setting up the Mekong Committee in 1957. However, during the Cold War era, the Mekong region witnessed numerous instances of intensified conflicts including the Vietnam war, Sino-Vietnam war, civil wars in Cambodia, and conflicts between Thailand and Vietnam, which caused states to pursue national interests over regional. Dinar et al. argues that these tensions delayed and disrupted the process of reaching cooperative, mutually beneficial agreements. In fact, the “hostility … (began) to yield to dialogue only in the 1990s” (Dinar et al., 2007:231).

The inactive, and previously irrelevant, Mekong Committee (or the Interim Mekong Committee[1]) regained prominence in the 1990s. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) was established in 1995, marking a key phase in hydropolitics in the Mekong region. Jacobs goes as far as to claim that launching the MRC indicated a “milestone in international water resources management treaties” (2002:360). The key objective of the MRC is noted as “to continue to cooperate and promote in a constructive and mutually beneficial manner in the sustainable development, utilization, conservation and management of the Mekong River Basin water and related resources … for social and economic development and the well-being of all riparian States, consistent with the needs to protect, preserve, enhance and manage the environmental and aquatic conditions and maintenance of the ecological balance exceptional to this river basin” (MRC, 1995:1-2)

One of the most peculiar features of the cooperative attempts in the Mekong Basin is that China, the primary upstream riparian, is not a part of it. In the initial years, China was not invited by riparian states to cooperate because the new Chinese government under Mao (People’s Republic of China) was not yet recognised by the United Nations as the ruling body. Later, when China was offered membership, the country rejected and agreed to be merely a ‘dialogue partner’ in the MRC. Ho explains this was because China “does not want to be subjected to the MRC’s provisions on aquatic environmental issues and restrictions on dam building” (2014:8).

In the two decades after the installation of the MRC, the Mekong region experienced significant social, economic, and environmental transformations. These changes produced several incidents of conflicting interests among the member states. Most of these incidents emerged from reduced waterflow and disgruntlement over dam construction over the Mekong, both of which negatively affected the agricultural industries, fisheries, and local communities (Gerlak et al., 2014). Some scholars praise the MRC for mitigating the escalation of these mild disagreements or non-cooperative behaviour into fully-fledged conflicts while others have claimed that these tensions are indicative of future conflicts, or even wars (Jacobs, 2002; Chellaney, 2011). Moreover, these scholars have pointed out that dam construction and proposals for the same are primarily carried out by the non-member upstream riparian states, especially China.

Because of the Mekong’s well-suitedness for hydropower development, it played a key role in China’s hydropower ambitions (Backer, 2007). Prior to 1991, China proposed the construction of 15 dams for hydropower generation along the Upper Mekong (Dinar et al., 2007:235). As of 2014, China had built seven dams on the river, and proposed plans to build 21 more. The construction of these dams, predictably, had negative repercussions in the lower Mekong basin.

Although the lower Mekong states have raised concern against Chinese hydropower projects, China has consistently defended its position and actions claiming that the construction of the dams benefits the downstream riparian states through flood control and hydropower generation (Backer, 2007). Despite the weak premises of these claims, the MRC members have not taken severe action against China; possibly because China has invested and developed in dam-building projects in the downstream countries as well (Ho, 2014). However, it is unlikely that the interests of the downstream riparian states can be ignored for long. Hydropolitics in the Mekong region are likely to change course in the future.

Understanding the hydropolitics of the Ganges and Mekong basins

The breakdown of events in the Ganges and Mekong basins clearly demonstrate that hydropolitics is not linear or rational. In the Ganges, the escalation of tension in an already hostile region after the occurrence of a conflictive event – plans to build the Farakka barrage in 1951 – was not dealt with by state violence. Instead, it was followed with various attempts to cooperate, which time after time were violated by the upstream hegemon, India. Whereas, in the Mekong, cooperation attempts were undertaken in a region characterised by historic enmity without a conflictive event serving as the motive. However, the weak premises of the cooperative agreement, along with non-cooperation from upstream neighbour China, does not completely erase the possibility of conflictive events in the basin. Hence, neither of the cases can be reduced to either ‘conflict’ or ‘cooperation.’

While rationalist theories may not be able to explain inconsistent state behaviour, a constructivist lens on the hydropolitics in Asia can offer a more appropriate insight. The essay will now attempt to understand the hydropolitics of the Ganges and Mekong basins by reviewing the domestic political makeup of the regional upstream hegemons, India and China.

Domestic political makeup

According to Russell and Wright, in the context of international politics, “an event can neither be predicted nor controlled unless account is taken of the circumstances which preceded it within each of the states involved” (1933:555). This perspective has been accepted by scholars in hydropolitics as well (Dinar et al., 2007). Frey explains that “a nation’s goals in transnational water relations are usually the result of internal power processes, which may produce a set of goals that does not display the coherence, transitivity or “rationality” assumed in many analyses of transparent national interest” (1993:63).

Domestic politics is inarguably a far-reaching and vague topic, especially in India and China. Hence, this essay will look into three main components of domestic politics: regime type, economic system, and role of non-state actors.

- Regime type

Since its independence in 1947, India has functioned as a constitutional democracy. This democratic model sustained through the following years with the INC (Indian National Congress) being the main political party in power. However, the late 1960s saw the emergence of alternative political parties in the national front. Viewing this as a threat to the INC, in 1975, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed a ‘national emergency’. From 1975 to 1977, India experienced an “authoritarian episode” where democratic practices were reversed and the democracy was at risk (Heller, 2000:492). However, since the withdrawal of the state of emergency, democracy in India continued to prosper, and has only strengthened over the years.

China’s regime or governance structure has gone through various transformations since the mid-twentieth century. The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949 by communist leader Mao Zedong. This period of autocratic rule witnessed dramatic authoritarian campaigns such as the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Following the death of Mao in 1976, the governance model experienced a subjugation of its autocratic regime. Even though this did not indicate a shift to democracy, subtle democratic values were infused into the regime. This included political and governmental changes, such as the implementation of direct elections in the village councils and local People’s Congress. This led to the creation of a hybrid regime in China. Panda describes it as a regime where “democratic elections replaced authoritarian sentiments, but the firmness of … one-party control was still felt behind the pretence of elections” (2010:47).

The regime type in both India and China played a role in defining its state interests and behaviour. In the context of India, as alternative political parties emerged, the existing government’s incentive to appeal to citizens, or voters, in attempt to influence elections strengthened. Kalbhenn suggests that leaders in a democracy have an “incentive to provide public goods in order to survive in office” (2009:66). Hence, the government is most likely to take positions or actions that are most desired by the voters. And in the case of India in the Ganges, this meant acting primarily for the benefit of its own people by building the Farakka barrage.

In China, from 1949 up until 1976, the state’s interests were defined by Mao’s priorities, and relied upon his approval (Zheng, 2013). Thus, Mao’s personal visions steered domestic policy and state behaviour. As Mao’s developmental strategy demonstrated little interest in the Mekong region in China, the region did not witness significant changes during his time (Dinar et al., 2007; Backer, 2007). After Mao’s rule, the national interests reflected the priorities of a few political elites of the CCP (Mesquita and Siverson, 1995). These leaders showcased an increased interest in the Mekong River for its hydraulic potential, which will be noted in the next section.

- Economic system

The Indian economy after independence was popularly known as the “Nehruvian model of mixed economy”(Singh, 2012:243). It comprised a primarily agricultural economy that was heavily controlled and regulated by the state (Kohli and Singh, 2013). At the time, the key motive of the Indian state was to end mass poverty and famine in the country. This eventually led to increased exploitation and demand for water resources to grow the predominantly agricultural economy (Singh, 2012). However, the failure and inefficiency of this socialist-inspired economic model eventually led to the Green Revolution in the 1960s, and intensive liberalisation of the economy in the 1990s (Klein and Palanivel, 2000). India experienced a shift from “a reluctant pro-capitalist state with a socialist ideology” to “an enthusiastic pro-capitalist state with a neoliberal ideology” (Kohli and Singh, 2013:9). As a result, economic activities accelerated, along with the exploitation of resources (Mall et al., 2006).

The pattern of economic transitions in China slightly coincides with that in India. Mao’s rise to power marked a shift from the romantic vision of “harmony between heaven and humans,” to Mao’s vision that “man must conquer nature” (Chellaney, 2011:59). Accordingly, under Mao’s rule, China’s economy was characterised by a Marxist-inspired economic system, where the exploitation of resources was a definitive aspect (Brown, 2012). The centrally planned agrarian economy did not allow private firms or foreign firms to function and limited foreign trade. However, the period was characterised by mass starvation and poverty. In fact, according to Deng, “the economy was virtually on the brink of total self-destruction with the standards of living among ordinary people pushed back decades” (2000:6). With the end of the Maoist period and the eventual fall of communism, the socio-economic environment underwent a wave of liberalisation. The resulting trade liberalisation and an open market saw an acceleration of economic activities and a resulting increase in economic growth.

Similar to regime types, an insight into the economic systems and their goals presents a clearer understanding of India and China’s behaviour. The Farakka barrage was built by the Indian government in pursuit of development in the Ganges region and the country. The main purpose for building the Farakka barrage was to improve navigability to the Kolkata port, increase water flow in West Bengal for farming, and sustain activities and livelihoods in the two main cities, New Delhi and Kolkata (Elhance, 1999). Hence, the economic interests of the country influenced its behaviour in hydropolitics.

While the Mekong received little attention under Mao, the CCP administration actively pursued liberalisation of the economy and resorted to water resources, especially the Mekong, for fuelling industrial activities and hydropower generation (Chang et al., 2010). Wen Jiabao stated in 2000, “in the twenty-first century, the construction of large dams will play a key role in exploiting China’s water resources, controlling floods and droughts, and pushing the national economy and the country’s modernisation forward” (Chellaney, 2011:70). Therefore, although the Mekong was largely unattended during Mao’s rule, the CCP administration’s aggressive attempts to expand the agricultural economy of China significantly influenced its engagement with the river.

- Role of Non-state actors

Non-profit and voluntary organisations advanced in India after the Indian government installed the Central Social Welfare Board in 1953, a platform to fund and foster the development of NGOs in independent India. The following years witnessed a steady increase in the work of NGOs. However, it was in the post-emergency period that India witnessed a dramatic escalation of NGO activity.

NGOs in India played a crucial role in addressing issues of water pollution and degradation. In the initial years, the government paid little or no attention to issues of biodiversity degradation and water pollution. As a response, NGOs, along with individual activists, used the media and other campaigning platforms to highlight the government’s neglect. Hensengerth states that, eventually, these NGOs successfully “used the court system to compel government agencies and industries to comply with existing legislation” (Hensengerth and Zawahri, 2012:292).

In China, NGOs dramatically increased after the end of Mao’s rule. The presence of a relatively more suitable legal system, greater awareness of citizen’s rights among civilians, and a diminishing of the CCP’s power, aided the development and growth of NGOs (Panda, 2010). In the 1990s, the deteriorating environmental conditions led to the increased participation of NGOs in environmental matters. Hensengerth and Zawahri explains that NGOs were relied upon to counter bureaucrats’ lack of technical proficiency (2012:275). In addition, the construction of dams along the Upper Mekong, “prompted Chinese NGOs (prominently an organization called Green Watershed) to advocate for greater transparency and participatory decision-making in water resource development planning” (Fox and Sneddon, 2006:187). Increased NGO investigation and activity on corruption, biodiversity degradation, and pollution in the Mekong eventually led to improvements in the national environmental legislation (Hensengerth and Zawahri, 2012).

When it comes to non-state actors, NGOs, have played a crucial role in environmental and water policies in both China and India. Even though NGOs did not explicitly work towards addressing international freshwater concerns, in both cases the respective downstream riparian states have enjoyed spill over benefits. To elaborate, “environmental DNGOs and policy entrepreneurs … (did) what the weaker downstream states have been unable to do: influence national and local governments of the dominant upstream state to improve water quality and protect biodiversity” (Hensengerth and Zawahri, 2012: 293). Thus, NGOs have unintentionally influenced the environmental policies around transboundary waterbodies.

However, as mentioned in the case studies, the major topic of contention in both China and India was not environmental degradation, but the quantity of water flowing into the downstream states – the reduced flow from unilateral dam construction and hydropower projects. This highlights the selectivity of India and China’s engagement with NGOs. In China, NGOs are mainly sponsored by the government. Thus, they work within the interests of the government and their role as watchdog of state policies is limited or non-existent. This implies that even though NGOs may be discontent with issues of water shortages or flooding in downstream states, they are unlikely to object to the government’s projects.

Similarly, in India, Banerjee (1999) notes that in the 1960s, a prominent Indian engineer, Kapil Bhattacharya, predicted that the Farakka barrage was likely to cause flooding in the Ganges basin. However, because it conflicted with the state’s interests, his criticism was maligned by both the government and media. Moreover, although numerous NGOs operate in the Ganges, there has been no visible activism for peace between India and Bangladesh in regard to the Farakka barrage (Faisal and Nishat, 2000).

A summary of observations

It is evident from the above review that domestic political makeup has contributed to the alteration of state interests, which in turn has impacted their actions and behaviour in hydropolitical affairs. The contribution can be summarised into three main observations:

Firstly, both India and China’s regime models had a strong bearing on framing their interests in transboundary waters. Being a democracy, the Indian state prioritised the interests of the citizens over the concerns of its downstream riparian. Thus, it executed unilateral projects on the Ganges, and belittled or violated the agreements signed with Bangladesh when the interests were at stake. Whereas in China, initially Mao’s interests were supreme. Thus, his lack of interest in the Mekong region clarifies to an extent as to why the Mekong was unattended in hydropower development strategies. However, after Mao’s rule, national interests reflected the interests of the political elite. As this clique of leaders were interested in the Mekong for its hydraulic potential, development in the region became a national interest.

Secondly, the economic systems of both countries influenced the management of and development on transboundary waters. Initially, both India and China, had a socialist or Marxist-inspired economic model, with limited privatisation and foreign interaction. However, through a series of liberalising reforms, both countries – currently, the powerhouses of Asia – pursued maximum utilisation of their water resources. This also included unilateral dam or hydropower constructions, which negatively affected downstream states.

Thirdly, relevance and enthusiasm of non-state actors reflected on the governments’ attention to pollution and biodiversity degradation. In both countries, environmental NGOs and activists played a significant role in pressurising the governments to revise existing environmental policies and legislation. Additionally, there is a lack of NGO activity addressing issues of dam construction and low waterflow in the neighbouring downstream states in the Ganges and Mekong basins. This also parallels with both governments’ lack of concern for the negative repercussions of their unilateral projects in both transboundary waters.

Even though the three components of domestic politics may not have explicitly or intentionally determined each country’s position in their respective water interactions, their influence on domestic policies hydropolitical state behaviour is apparent. Thus, inadvertently, the transformation in state identities and interests, which were fostered by changes in domestic politics, have had a noteworthy bearing on state behaviour in transboundary water politics.

Conclusion

Hydropolitics is unique and complex. Although dominant discourses of hydropolitics fixate on rationalist theories of conflict or cooperation, they fail to provide a satisfactory explanation of the vastness and breadth of state behaviour in hydropolitics in the real world. This essay has undertaken the task of framing an alternative constructivist lens to understand hydropolitics. By drawing upon the cases of hydropolitics in the Ganges and Mekong basins, the essay has demonstrated that a review of the domestic political makeup – mainly the regime type, economic system, and role of non-state actors – of the upstream hegemons, India and China, provides a more appropriate and inclusive explanation of state behaviour than popular rationalist theories can.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the relevance of realist and liberal schools in theorising how states are expected to act in the international system – i.e., prediction of state behaviour – is unchallenged by this essay. As stated by Slaughter, “Constructivism is not a theory, but rather an ontology” (2011: para. 19). Hence, the constructivist lens proposed in this essay, serves solely as a foundation for explaining why states behave in the ways predicted by the realist and liberal schools of thought, as opposed to serving as an alternative to both theories.

References

- The Interim Mekong Committee was set up when Cambodia withdrew from the Mekong Committee due to the rise of the Khmer Rouge

Bibliography

Backer, E.B. (2007). The Mekong River Commission: Does it work, and how does the Mekong Basin’s geography influence its effectiveness? [Online] Available from: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/33627/ssoar-suedostaktuell-2007-4-backer_bruzelius-The_Mekong_River_Commission_Does.pdf?sequence=1

Banerjee, M. (1999). A report on the impact of Farakka Barrage on the human fabric, South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People

Brown, K. (2012). The Communist Party of China and ideology, China: An International Journal, 10(2).

Carius, A. et al. (2005). Managing Water conflict and cooperation, State of the World (Routledge)

Cascao, A. E. et al (2015) The Ganges-Brahmaputra River basin, Transboundary water management and the climate change debate (Routledge)

Chang, X. et al (2010) Hydropower in China at present and its further development, Energy, 35(11). (Elsevier)

Chellaney, B. (2011) Water: Asia’s New Battleground, (Georgetown University Press)

Daoudy, M. and Kistin, E.J. (2008). Beyond Water Conflict: Evaluating the effects of international water cooperation, [Online] Available from: http://www.academia.edu/28684727/BEYOND_WATER_CONFLICT_EVALUATING_THE_EFFECTS_OF_INTERNATIONAL_WATER_COOPERATION

Deng, K. (2000). Great leaps backward: poverty under Mao [Online] Available from: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/652/1/Maoist_growth-Final.pdf

Dinar, A. et al. (2013) Bridges Over Water: Understanding Transboundary Water Conflict, Negotiation and Cooperation, (World Scientific), first edition, 2007.

Elhance, A. (1999). Hydropolitics in the Third World: Conflict and Cooperation in International River Basins, (US Institute of Peace Press)

Faisal, I.M. & Nishat, A. (2000). An assessment of the institutional mechanisms for water negotiations in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna System, International Negotiation 5(2).

FAO (1984). Systematic Index of International Water Resources Treaties, Declarations, Acts and Cases, by Basin, Vol. I and Vol. II (United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation)

Fox, C. and Sneddon, C. (2006). Rethinking transboundary waters: A critical hydropolitics of the Mekong basin, Political Geography, 25

Frey, F (1993). The political context of conflict and cooperation over international river basins, Water International,18

Gerlak, A. et al (2014) A study of conflict and cooperation in the Mekong river basin: how issues and scale matter, FLASCO-ISA Global and Regional Powers in a Changing World conference, Argentina

Gleick, P.H. (1993). Water and conflict: Fresh water resources and international security, International Security, 18(1)

Heller, P. (2000). Degrees of democracy: Some comparative lessons from India, World Politics, 52(4)

Hensengerth, O. & Zawahri, N.A. (2012). Domestic environmental activists and the governance of the Ganges and Mekong Rivers in India and China, International Environmental Agreements, 12

Ho, S. (2014). River politics: China’s policies in the Mekong and the Brahmaputra in comparative perspective, Journal of Contemporary China, 23(85)

Hossain, I (1998) Bangladesh-India Relations: The Ganges water-sharing treaty and beyond, Asian Affairs, 25(3)

Jacobs, J.W. (2002). The Mekong River Commission: transboundary water resources planning and regional security, The Geographic Journal, 168(4 )

Kalbhenn, A. (2009). A river runs through it: Democracy, international interlinkages, and cooperation over shared resources [Online] Available from: https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/151942/eth-1209-02.pdf

Klein, L.R. & Palanivel, T. (2000). Economic reforms and growth prospects in India [Online] Available from: https://crawford.anu.edu.au/acde/asarc/pdf/papers/2000/WP2000_03.pdf

Kohli, A. & Singh, P. (2013). Routledge Handbook of Indian Politics, (Routledge)

Mall, R.K. et al. (2006). Water resources and climate change: An Indian perspective, Current Science 90 (12)

Mesquita, B.B.D & Siverson, R.M. (1995) War and the Survival of political leaders: a comparative study of regime types and political accountability, The American Political Science Review, 89 (4)

Mirumachi, N. & Zeitoun, M. (2008). Transboundary water interaction I: reconsidering conflict and cooperation, International Environment Agreements, 8

MRC (1995) Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin, Mekong River Commission

Panda, J.P. (2010). China’s Regime Politics: Character and Condition, Strategic Analysis, 34(1)

Rahaman, M.M (2009) Principles of Transboundary Water Resources Management and Ganges Treaties: An Analysis, Water Resources Development, 25 (1)

Russell, J.T. & Wright, Q. (1933). National attitudes on the Far Eastern Controversy, American Political Science Review 25.

Singh, K (2012). Nehru’s Model of Economic Growth and Globalisation of the Indian Economy, South Asian Survey (SAGE Publications)

Slaughter, A. (2011). International Relations, Principal Theories [Online] Available from: https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/slaughter/files/722_intlrelprincipaltheories_slaughter_20110509zg.pdf

Solomon, H. & Turton, A. (2000). Water Wars: enduring myth or impending reality (African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes)

Stucki, P. (2005). Water Wars or Water Peace? Rethinking the nexus between water scarcity and armed conflict, [Online] Available from: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/20609/PSIS-OccPap-2_2004-Stucki.pdf

Swain, A. (2004). Managing Water Conflict: Asia, Africa and the Middle East (Routledge)

Turton, A. (2002). Hydropolitics: the concept and its limitations, Hydropolitics in the developing world: A southern African perspective, African Water Issues Research Unit, ed. Henwood, R. and Turton, A. [Online] Available from: http://www.internationalwaterlaw.org/bibliography/articles/hydropolitics_book.pdf

UNDESA (2014). Transboundary Waters, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [Online] Available from: http://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/transboundary_waters.shtml

Wolf, A. & Hamner, J. (2000). Trends in trans-boundary water disputes and dispute resolution, Water for Peace in the Middle East and Southern Africa, (Green Cross International)

Zheng, Y. (2013). Contemporary China: A History since 1978 (John Wiley & Sons)

Devika Nambiar received her undergraduate degree in Development Studies and International Relations from the University of Westminster in 2017. She is currently working as a communications consultant and writer specialising in the arts and culture, humanitarian, and education sectors.